Trevor Baylis believed that the key to success was to think unconventional thoughts.

It was this mindset that saw him develop his clockwork radio after hearing about the problems of educating African people about HIV and Aids.

It enabled those in remote areas without electricity, or access to batteries, to get the information that could save their lives.

But despite the success of this, and other inventions, Baylis never made a great deal of money from his many ideas.

Trevor Graham Baylis was born in Kilburn, north-west London, on 13 May 1937 and brought up in Southall, Middlesex.

His father was an engineer and the young Trevor was introduced to a Meccano building set which inspired his fascination with mechanical things.

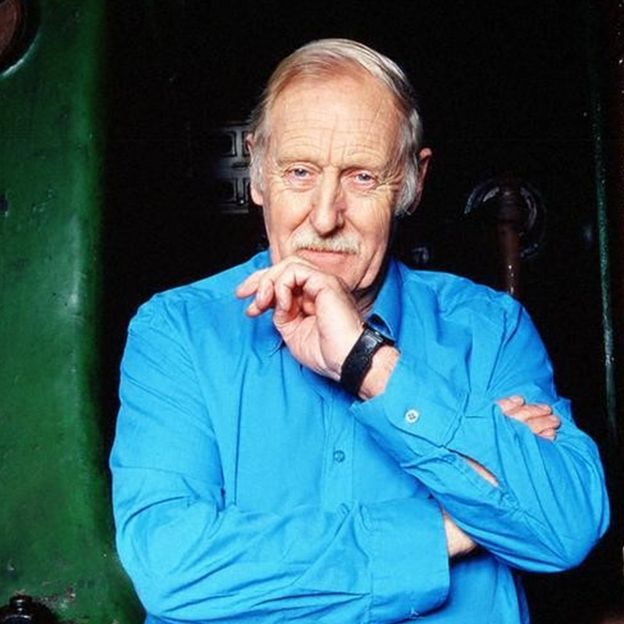

TREVOR BAYLIS

TREVOR BAYLIS

The young Baylis supplemented the family income by working on a local milk round which saw him getting up at 3am each morning.

He was also a proficient swimmer and narrowly failed to qualify for the 1956 British Olympic team, something he greatly regretted.

He left school at 15 to work in a local soil mechanics laboratory, attending day-release courses in mechanical and structural engineering.

Baylis did his National Service as a physical training instructor in the Army. When he left, he got a job as a salesman with Purley Pools, one of the first companies to sell free-standing swimming pools.

Recycled

Because he was a good swimmer he demonstrated the pools at shows, attracting crowds of potential customers.

He went on to form an aquatic stunt troupe which saw him diving into a glass-sided tank and also performing an underwater act in a Berlin circus.

"It was fantastic," he later recalled. "I made enough money to buy a plot of land and and build the house of my dreams

The death of a close friend in a trapeze accident prompted him to begin developing products for people with disabilities.

"Her death broke my heart," he said. "You realise disability is only a banana skin away."

He developed a range of products under the Orange Aids label, including one-handed scissors and devices for opening bottles and cans.

But although the products were successful they failed to make his fortune. The costs of getting a patent were prohibitive and companies were able to copy his inventions.

Aids

"I went into the deal which I thought would secure the future of Orange Aids with culpable impetuosity. I had been used to doing business on a handshake and my word of honour, and I made the error of actually believing what the men in the pinstriped suits told me."

It was to be something that dogged his career but he remained philosophical, saying he always followed his heart.

"It's not about the money," he said in a 2004 interview. "I can't imagine anything worse than looking at a computer all day then glancing at your watch because there is an important meeting about the men's toilets at 3pm."

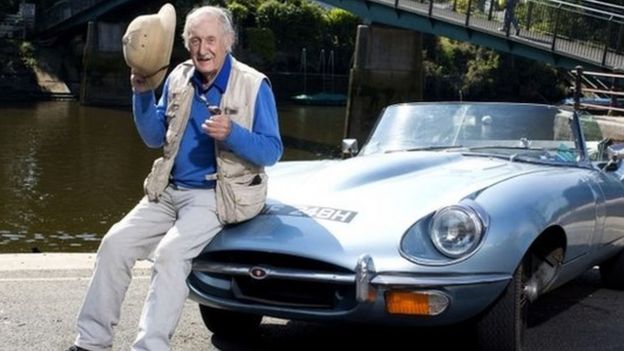

REX FEATURES

REX FEATURES

The idea for his wind-up radio came while he was watching a TV programme in 1991 about the spread of Aids in Africa and a proposal to tackle it by broadcasting educational programmes on the radio.

Baylis later said he went into a reverie imagining himself as a colonial settler, nursing a gin and tonic and listening to a wind-up gramophone.

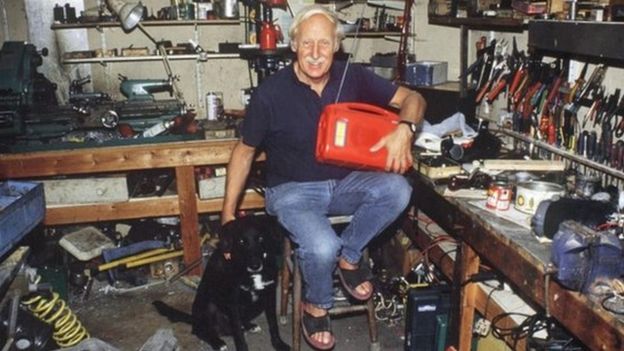

The image encouraged him to go to his workshop, which was filled with disassembled domestic appliances and, within half an hour, he had a working prototype of his clockwork radio.

Learning from his Orange Aids experience, Baylis patented the project and went in search of a manufacturer. Everyone he approached turned him down.

Failed

It was an appearance on the BBC's Tomorrow's World programme in 1994 that finally brought his invention to public attention.

"Everyone thought I was a genius whereas, up to then, I was just another silly little man."

Further publicity followed. He was awarded the BBC Design Award for Best Product and Best Design in 1996 and met Nelson Mandela and the Queen.

A South African company began manufacturing his radio in 1997 but, once again, Baylis failed to make a great deal of money from the product.

"My mistake was that I trusted the people I was working alongside. Large corporations can circumnavigate your patents."

He eventually lost control of his design and the company, somewhat ironically, began making cheaper wind-up radios for a Western market increasingly concerned with green issues.

Undaunted, Baylis continued coming up with new ideas including a shoe that could generate electricity as the wearer walked.

Disarray

He demonstrated them with a 100-mile hike across Namibia to raise money for a landmine charity.

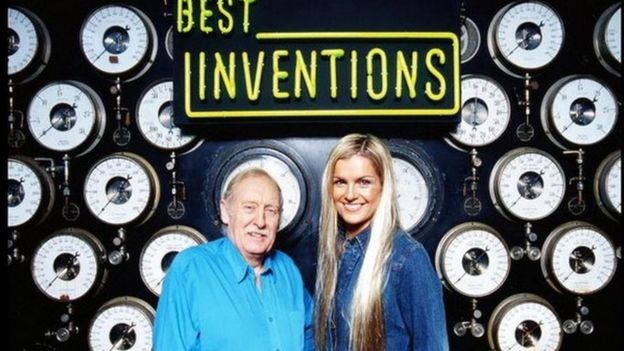

He also set up the Trevor Baylis Foundation to encourage and develop new products and, importantly, advise inventors how to protect their intellectual property.

He was awarded an OBE in 1997 and collected a number of honorary degrees from leading universities.

REX FEATURES

REX FEATURES

Trevor Baylis never married, believing that no wife would put up with the disarray in which he liked to work.

He strongly believed that Britain was cavalier in its treatment of inventors, meaning many products disappeared overseas.

"Inventors do not get enough credit," he said. "I always say, art is pleasure, invention is treasure.

"Nobody seems to know who invented the paper clip but everybody has one."

No comments:

Post a Comment